The Unangax̂: Alaskan Slaves of the Pribilof Islands

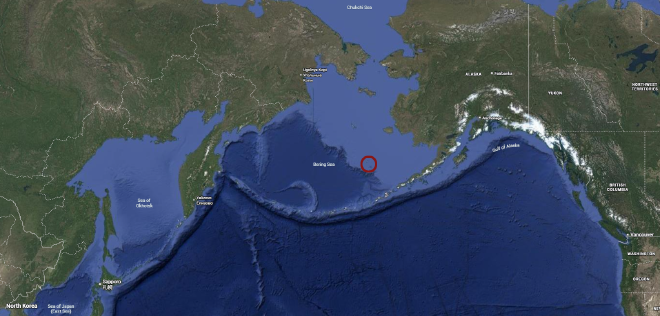

In 1786, a Russian fur trader reached a pair of islands in the Bering Sea while hunting for northern fur seals. With no permanent inhabitants, the islands were a fertile breeding ground for the animals, whose pelts were highly prized in China and Europe.

//What was once a seasonal hunting trip became a permanent life To capitalize on this untapped resource, the trader and his company kidnapped Unangax̂ (Aleut) men from their villages in the Aleutian Islands (200+ miles away) and transported them to the Pribilof Islands to harvest the seals. The men were abandoned on the islands with minimal supplies, forced to survive without oversight or recourse. They had to explore the islands, build their own shelters, and find their own food to survive.

Eventually the traders returned with even more Unangax̂ slaves and company enforcers to manage the islands. For the next 80 years, the Russian seal fur company continued to raid the indigenous villages for more laborers while abusing their current slaves. New, managed, interracial families began to grow on the island while the wider Unangax̂ population collapsed. It was organized, documented, and sustained over generations.

//Two years after the American Civil War In 1867, the United States bought Alaska from Russia for $7.2 million. The system continued. The people on the island didn’t suddenly become autonomous. The rules didn’t change. From 1870 to 1910 the federal government leased the Pribilof Islands to private companies who ran the seal harvest and further controlled the daily life of the Unangax̂.

//Slavery, with extra steps In 1910 the U.S. government took over control of the islands and the seal harvests directly. The language changed (protection, stewardship, wardship), but the structure stayed the same. Work was assigned. Food and health care were controlled. Permission was required to leave. The island functioned as a federal work camp built around seals.

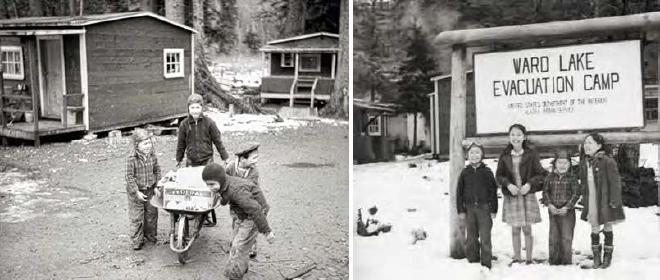

//Then along came WWII In 1942, after Japan attacked Dutch Harbor and occupied Attu and Kiska, the U.S. decided the Pribilof Islands were a liability. Not because the residents were a threat, but because they were inconvenient to defend. Their solution was relocation. Entire communities were put on ships with little notice. They were sent to internment camps in Southeast Alaska run by the government, 1,500 miles from the Pribilof Islands. Across the gulf of Alaska, with very different climates and cultures. Places like abandoned canneries and old mining camps. Locations that were never meant for long-term habitation.

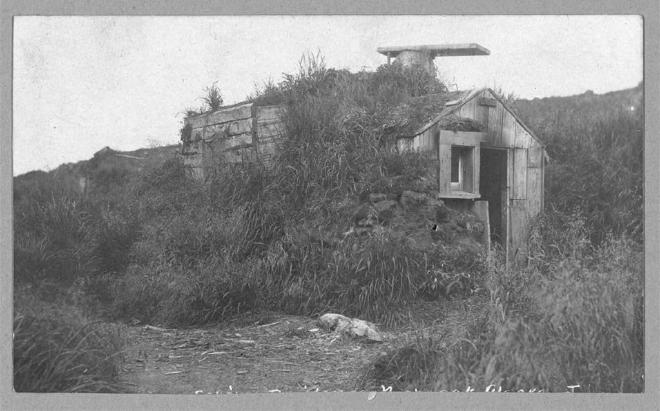

//On top of it being one of the harshest climates The buildings were overcrowded, damp, and unheated. Sanitation was poor. Medical care was minimal. Food was inadequate. Families from different islands were mixed together. Elders were separated from familiar environments. Children were placed in conditions where disease spread quickly. Tuberculosis, pneumonia, and influenza were common. The death rate in the camps was high, especially among elders. Oral histories were lost as elders passed away.

While in the camps, the Pribilof Islands were stripped. Homes were vandalized. Churches were looted. Personal belongings were taken or destroyed. In 1945, when residents were finally allowed back after the war, many found their houses damaged or unlivable. And they didn’t come back to freedom. They were returned to the same federally controlled system they had been removed from. Permission to leave was still required. Work was still assigned. Food and medical care were controlled. The seal harvest still dictated life.

//The first Star Wars movie came out before the federal government fully withdrew This lasted into the 1960s. Mandatory labor did not end until 1966. The right to leave without permission arrived in 1967. Nearly two hundred years after the first forced relocation. A full century after America took control. The U.S. government did not fully withdraw until the early 1980s. That’s when people gained control over housing, work, and local governance. That’s when the island stopped being managed as an extraction site and started operating as a community.

During the years of the fur seal harvest, the U.S. made far more than it paid for Alaska itself. Conservative accounting shows the lease system alone repaid the purchase price before 1910. Broader estimates put total U.S. earnings from Pribilof seal skins at around $160 million (~$5 billion today). At the same time, the Unangax̂ population was decimated. Entire villages were wiped out. Estimates suggest that by 1910, the Unangax̂ population had fallen to less than 10% of its pre-contact size.

//SOURCES #

VIDEOS & ORAL HISTORIES #

- Brief History of the Unangax̂ People

- Unangax̂ World War II History

- War Crimes Against the Unangax̂ People

- Interview with Unangax̂ Elder General Jake Lestenkof

- Growing up on St George Island

- On his family’s displacement

- Pribilof Islands historical films

- People of the seal

- The tiny Alaskan island fighting for its future

WIKIPEDIA ARTICLES #

WEBSITES #

- https://www.aleut.com/about/

- https://www.apiai.org/

- https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/wartime-internment-native-alaskans

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/aleu-mobley-intro.htm

- https://www.nps.gov/aleu/learn/historyculture/unangax-history-and-culture.htm

- https://npshistory.com/publications/incarceration/personal-justice-denied/part2.htm

- https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/resource/document/pribilof-islands-preserving-legacy-2008

- https://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip_508-0z70v8b39n

- https://times.org/slaves-of-the-fur-seal-harvest/

- https://crushingcolonialism.org/the-untold-story-of-aleutian-survival-language-and-colonial-devastation/

BOOKS & PAPERS #

- Douglas W. Veltre: A Life in Aleutian Anthropology by David R. Yesner

- Russian Colonization of Alaska series by Andrei Val’terovich Grinëv

//AUTHOR’S NOTES #

Although often described in official records as ’laborers’, the Unangax̂ men and families on the Pribilof Islands were not free to leave, refuse work, or control their livelihoods. This meets the core definition of slavery. This history is not widely known, even among Alaskans. It is not taught in schools. It is not part of mainstream American historical narratives. I only know about it because I lived in Alaska and learned about it from elders that came to speak at my school. Their stories left a deep impression on me. Acknowledging this history is a step toward honoring their experiences.

//I refuse to let this be forgotten.